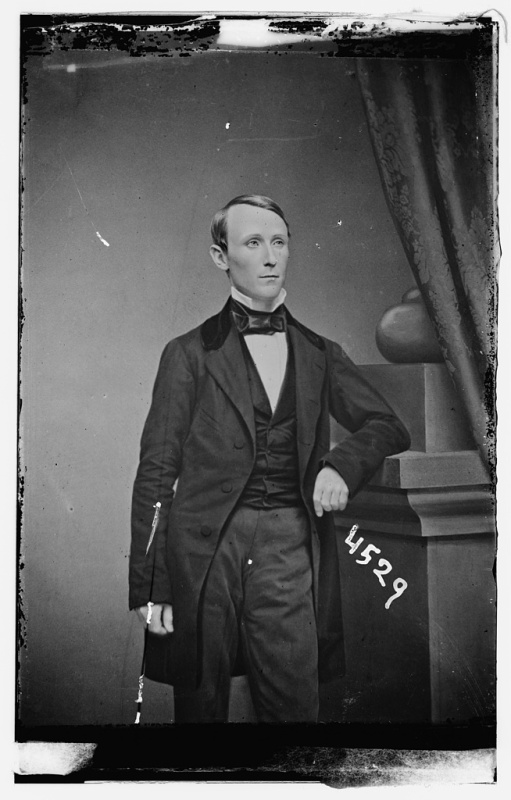

Phil Rice’s “Correct Method for the Banjo” (1858) gives us this striking vision of slavery carried south in the service of the Filibuster president, General William Walker:  The lyrics demonstrate the importance of African American music to the expatriate Filibusters:

The lyrics demonstrate the importance of African American music to the expatriate Filibusters:

I’m Off for Nicaragua

Such a gwine around de horn and a cotchin ob de cold,

And a waitin round de table on de white folks,

Such a scratchin ob de grabble, and a diggin ob de gold,

Oh de nigger likes to trabble wid de white folks.To de land,

Oh to de land,

To de land,

Oh to de land,

Oh, oh, oh, oh.

Oh fare you well my lub, now I bid to you adieu,

For I’m off for Nicaragua in de mornin.I stopped on de Isthmus my fortune for to try,

To sing dis song and play for Gen’l Walker,

Oh I neber shall forget until de day I die,

Dere was hard times den in Nicaragua.

To de land, &c.I struck em up a tune, and dey all begin to plance,

Dis music ebry one took great delight in.

It made em think of home when dey got thro’ de dance,

Oh dey’re de boys dats got de game for fightin.

To de land, &c.Dey blowed upon de fife, and beat upon de drum,

When dey found de Costa Ricans was advancin,

Gen’l Walker said, guess wed better let em come,

Dey shall hab a ball, to set em all a dancin.

To de land, &c.De little grey eyed man begin to call aloud,

De figures for to set de ball in motion,

We’ll furnish dem wid music and feel it mighty proud,

Now go in boys, and make em change dare notion.

To de land, &c.So we pull’d off our coats, and we rolled up our sleeves,

You ought to see de Costa Ricans trabble,

Jordan was a hard road dey all began to believe,

For de todder side dey gin to scratch a grabble.

To de land, &c.

This 1849 map demonstrates several sea routes from the Atlantic Coast to California, via South America’s Cape Horn and the Central American Isthmus; clearly, the transit route through Nicaragua offers much faster and somewhat more secure travel between New York and San Francisco:

(See here for a more detailed view of the complete map…)

(See here for a more detailed view of the complete map…)

When Walker assumed the presidency of Nicaragua, he re-established slavery there in 1856; “I’m Off to Nicaragua” notably presents the transit experience through the eyes (and music) of a slave character — that is to say, a caricatured “negro” persona from Phil Rice’s blackface stage show.

Setting aside the questions of authenticity and appropriation in 19th century racial delineation, then, this song outlines several popular conceptions of music’s role in national identity & global politics:

- The slave narrator is an essential part of the Central American transit, and supports the comfortable lifestyle of “de white folks”.

- African American music (esp. banjo tunes, given the source) reminds the Filibusters of “home” and stirs them to dance and carouse in high spirits.

- This music becomes an important part of morale in the outnumbered North American filibuster army, and in fact can help determine the course of battles.

- This same music provides a vital organizing force in military activities — in the case of this particular song, it even substitutes for combat. (“Dey shall hab a ball, to set em all a dancin.”)

- Said music creates such a powerful sense of national identity among the filibusters that the local Costa Rican army flees in disarray (presumably to the tune of “Jordan is a Hard Road” & other popular banjo songs), leaving Nicaragua to the North American forces… *

*(That’s just wishful thinking — actually, it was the cholera that did in the Costa Ricans.)

![1856-[Nicaragua - fillibusters reposing after the battle in their quarters at the convent]-3c08152v](https://civilwarfolkmusic.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/1856-nicaragua-fillibusters-reposing-after-the-battle-in-their-quarters-at-the-convent-3c08152v1.jpg?w=600&h=412) For more about William Walker’s various activities, including many (pro-filibuster) details about his battles with the Costa Rican-led allied armies, see Walker’s own account, The War in Nicaragua (published posthumously in 1860) and James Carson Jamison’s With Walker in Nicaragua (1909).

For more about William Walker’s various activities, including many (pro-filibuster) details about his battles with the Costa Rican-led allied armies, see Walker’s own account, The War in Nicaragua (published posthumously in 1860) and James Carson Jamison’s With Walker in Nicaragua (1909).  For more Walker materials, see this collection at the Tennessee State Library & Archives.

For more Walker materials, see this collection at the Tennessee State Library & Archives.

One Comment Add yours